After releasing The Trade Skirmish of 2018, a policy report on the early evidence on the economic effects of the tariff actions by the U.S. and global retaliation (http://glenn.osu.edu/research/) in April, I was asked to referee a family feud. What follows is an edited version of the question and an expanded version of my answer.

Good morning Mr. Hill,

I am trying to understand what factors led GM to close the plant in Lordstown, Ohio. My cousin and I argue about Donald Trump and his policies non-stop. My cousin says that Lordstown has nothing to do with steel tariffs and is the UAW’s fault for wanting higher wages. I say that steel tariffs were PART of the problem … I know that there are other factors, but I would like to know for sure what they were.

My extended answer to the family feud:

As expected with such a politically charged subject, the role of the Trump administration has dominated discussion over the Lordstown plant closure. I hate to be a typical economist about this, but: financial realities drove GM to close the plant, and this had almost nothing to do with politics. Both the Trump-lover and Trump-opponent are wrong.

The steel tariffs did not help Lordstown’s competitive position, but I’ve concluded that they were not the determining factor in the plant’s closing. The most significant cause of the shutdown is straightforward: the Cruze, Chevy’s budget sedan/hatchback model, was not selling. Companies cannot sell what consumers do not want; and factories will not produce products that do not sell. That is how market-based economies work.

Hold on, you might be asking, why not just build another vehicle in the plant instead of closing it for good? What prevents GM from assembling its new Blazer, a mid-sized SUV, in Ohio, rather than in a Mexican plant?

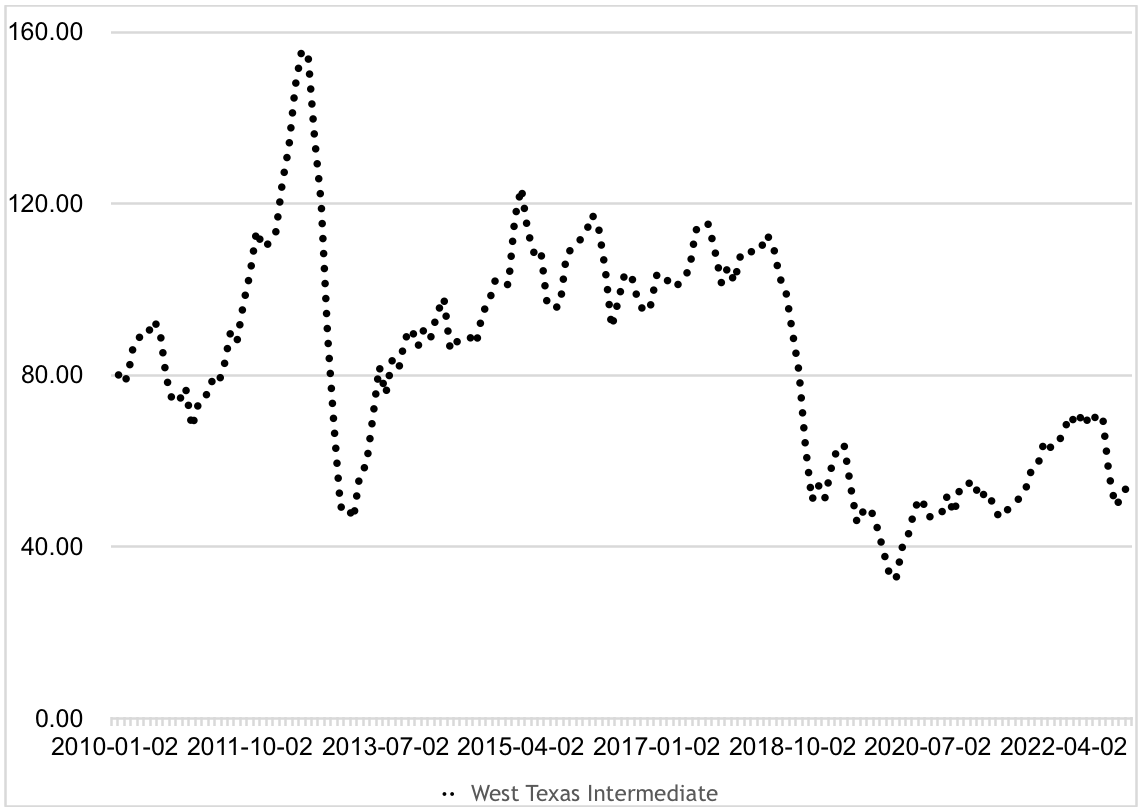

The answer lies in decisions that were made when Lordstown was retooled for the Cruze and its predecessor in 2010. Recovery from the Great Recession had just begun, and gas prices were high, resulting in demand for small, efficient sedans. (See Figure 1 below). Because profit margins are narrow on small cars aimed at the mass market, the company depended on a highly efficient assembly line and high-volume sales to earn its profits. Substituting volume for margin required building an inflexible assembly line that could only make the Cruze or close derivatives. Vehicle production efficiencies based on scale and inflexibility work well only as long as there is demand for at least two shifts of production.

GM added a third, or overnight, shift in Lordstown in 2011 to meet demand, resulting in the assembly of 231,732 cars. When three shifts were working the plant produced 1,300 vehicles a day. With two shifts the number declined to 1,000.1 The third shift worked away through 2016; after that, demand for the car began to drop and the third shift was let go. The second shift was terminated in June of 2018, leaving just the day shift. With only a single shift working, the plant was doomed. In November 2018, GM’s Lordstown was reported to be operating at 31 percent of capacity and not recovering it’s operating, or marginal, costs.2

Inflation-adjusted Monthly Price of a Barrel of West Texas Intermediate Crude Oil: January 2006 to February 2019. Expressed in terms of February 2019 prices.

Figure 1:

GM reopened Lordstown in 2010, as gas prices were in the midst of a half-decade rise. The expansion of fracking drove down oil prices in 2014, along with demand for fuel-efficient cars.

(Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) – Cushing, Oklahoma [MCOILWTICO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MCOILWTICO, March 24, 2019.)

Why did the Cruze stop selling?

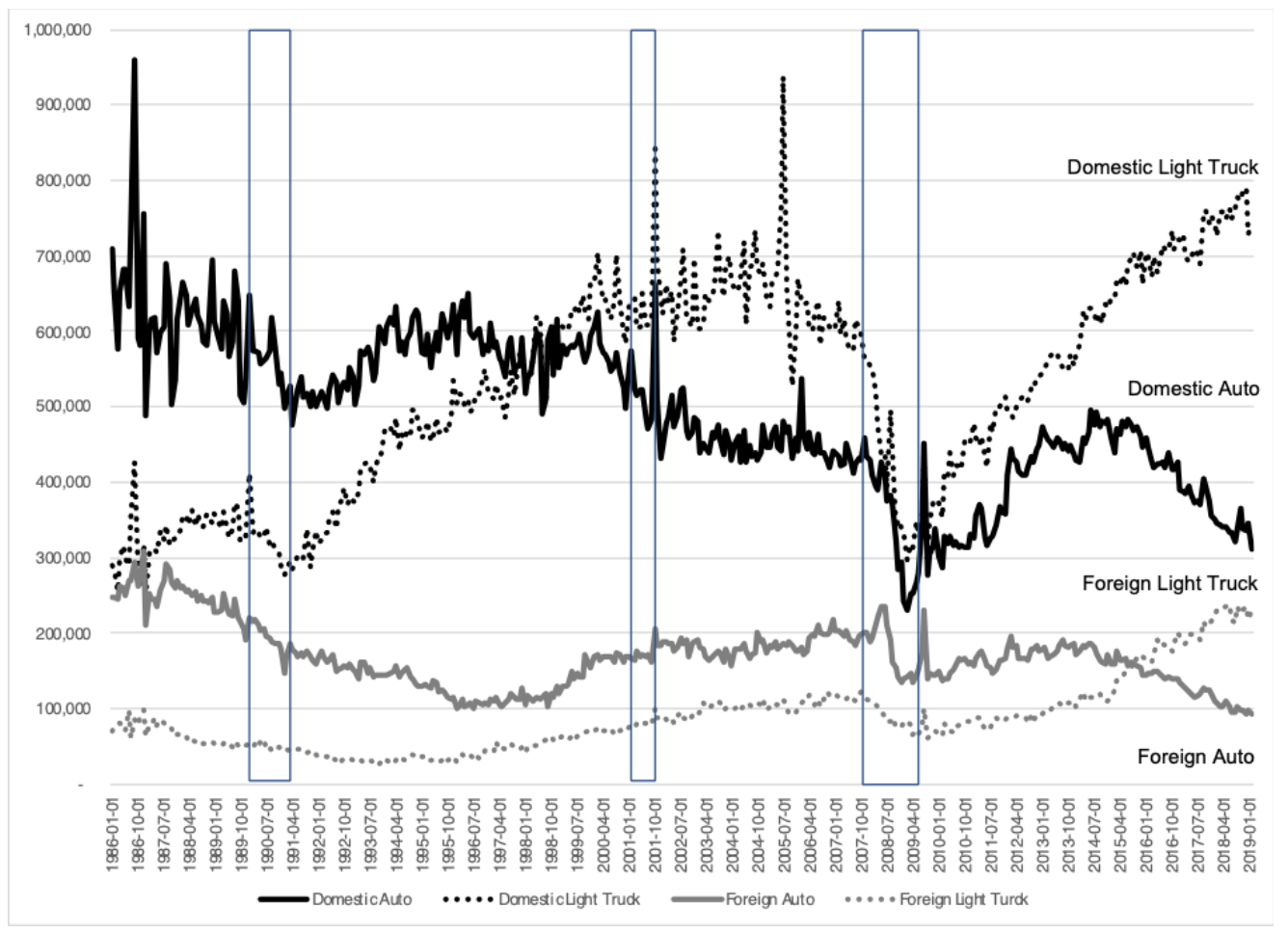

Sales of small, fuel-efficient, cars were stimulated by expensive gasoline and high Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. Unfortunately for plants that build small sedans, three market changes caused demand to crater. The first was the development of extremely fuel-efficient engines. Next came increases in the supply of oil produced by the fracking boom, resulting in a drop in the price of gasoline. The final nail in the coffin was a shift in taste from sedans to roomier and flexible Sport Utility Vehicles (SUVs). (see figure 2)

Monthly Sales of Foreign and Domestic Automobiles and Light Trucks from January 1986 to February 2019, seasonally adjusted. Recession periods are boxed.

Figure 2:

As the economy recovered from the 2008 Great Recession and gas prices fell, Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs), which are categorized as light trucks, became increasingly popular.

(Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Motor Vehicle Retail Sales: Domestic Autos [DAUTOSA], Domestic Light Truck [DLTRUCKSSA], Foreign Autos [FAUTOSA], and Foreign Light Truck [FLTRUCKSSA] retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FAUTOSA, March 24, 2019.)

Why didn’t GM put in a new vehicle in Lordstown?

So–this brings us back to our original question. Why not just retool the Lordstown plant to make SUVs? After looking at the data on the auto industry, I concluded that GM thinks that it has too much North American assembly capacity and is shutting down the three plants that are either the most expensive to operate or require the most investment to turn around.

GM announced the Blazer’s assembly in Mexico in June 2018, two months after the second shift in Lordstown was laid off, and the vehicle’s launch coincided with the closures of the Lordstown, Hamtramek/Poletown, and Oshawa, Ontario assembly plants. The timing of these announcements was a public relations nightmare; linking the Mexican launch and the Lordstown closing in the public’s mind and politicians’ mouths.

But …

The decision on where the Blazer was going to be assembled was most likely made two or three years before the 2018 announcement to accommodate capital equipment planning, purchasing, and final vehicle design. While the company could not predict falling gas prices, it was quick to realize that the market demand for fuel-efficient cars was dropping. GM spokeswoman Katie Amann told Bloomberg that the “company was planning the vehicle years ago when all of its SUV plants were running on three shifts. The Ramos Arizpe factory was the only assembly plant with enough capacity for the Blazer.” 3

The inescapable conclusion is that the Blazer’s assembly in Mexico was a decision that was in the works for several years—Trump had no influence one way or the other. And the shutdown in Lordstown had nothing to do with the opening in Mexico.

The union local in Lordstown is, or was, one of the best in GM’s system, and it positively affected the quality produced in the plant. However, productivity alone could not offset the cost of a new assembly line, and could not counter GM’s conclusion that the company had too much North American production capacity. The most expensive factories always lose in decisions such as this one.

All automotive assemblers currently face disruption—the motor vehicle assembly business has entered an era of both cyclical and secular decline. The foundation of Detroit’s problems rests on the fact that they have provided slim returns to stockholders, at a time when the companies need capital to invest in their future. Electronics and intelligence are growing parts of the bill of materials with good margins, and assemblers do not want to give that money away to their software suppliers. They also have to invest across 4 distinct areas of mobility—all related and, at the same time, all different:

- Traditional individually-owned automobiles with gasoline-fueled powertrains, enhanced with intelligence for safety and entertainment

- Individually-owned vehicles with electronic or hybrid powertrains

- Autonomous vehicles

- Per-ride mobility travel solutions rather than traditional vehicle ownership

GM CEO Mary Barra was correct when she told The New York Times’ The Weekly that GM is now a software company. GM is also an electric powertrain company, a mobility company, a motor vehicle assembly company, and an internal combustion engine company.

Hard decisions have to be made, and if the U.S. slips into a recession, the choices will become harder, with more assembly plants shutting down.

OK, now back to the family in the Mahoning Valley: buy each other a beer (or two). There are just some times when the markets beat politics. Also, get ready for more drinking because the UAW-GM negotiations began on July 16, and these plant closures are front and center in the talks.

If readers are interested in more on the corporate and personal challenges caused by the disruption in the motor vehicle industry and its impact on both GM and Lordstown, go to Hulu and watch The New York Times’ half hour news show, The Weekly, on this topic, The End of the Line: https://www.hulu.com/series/the-weekly-97cc2649-4298-4122-bf80-cabdf1332d65

FYI, this recommendation is not disinterested—I am interviewed on the program.

1Jeff Green, “Auto industry recovery generates third shifts at U.S. plants, more jobs,” Automotive News, January 21, 2012. https://www.autonews.com/node/427601/printable/print

2Joseph White and Nick Carey. “GM to slash jobs and production, drawing Trump’s ire,” Reuters, November 26, 2018, citing a report by automotive consultants LMC.

3David Welch, “GM to Build Chevy Blazer in Mexico, Risking Trump’s Ire,” Bloomberg, June 22, 2018.

4Sabrina Tarvernise, “The end of the line,” The Weekly, July 7, 2019